A while ago I came across this Solar System sampler in the Museum’s textiles store. It was uncanny – the arrangement of concentric rings was so familiar and immediately recognisable, but so strange when seen as a piece of Georgian embroidery.

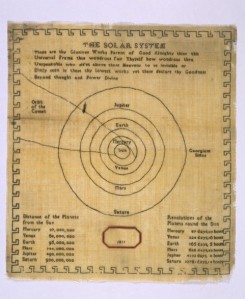

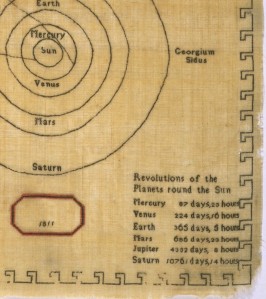

The sampler is a piece of linen 35cm tall and 35cm wide, with the title ‘The Solar System’ followed by five lines of text. At the centre is a large diagram of the six innermost planets orbiting the sun. At the bottom are two tables of data, either side of the date 1811. The design has been transferred onto the fabric with ink, creating a template for the embroiderer. However, only small areas have been completed in silk thread. Quite early in the project, this sampler has been abandoned.

The unusualness was reinforced by the other samplers in our collection, which bore familiar decorative alphabets and floral patterns. In the eighteenth century embroidery featured large in girls’ education. But practical uses like mending clothes and decorating soft furnishings paled in comparison to embroidery’s supposed moral benefits. Needlework required patience and concentration, and it kept women at home, focussed on a virtuous domesticity.[1] Most other samplers of this time show suitably ladylike subjects.

See the V&A website for several excellent histories of samplers.

The turn of the nineteenth century was an extremely exciting time in all the sciences, including astronomy. New telescopes and methods in the hands of enthusiasts kept surprising the world with new discoveries. In 1781, England’s foremost astronomer-composer William Herschel confirmed the existence of another planet, orbiting beyond Saturn. He named the star after his King and patron, George III.[2]

Four more planets were discovered between 1801 and 1804: Ceres, Pallas, Juno and Vesta. They were soon reclassified as ‘asteroids’. The census of comets, fixed stars and other galaxies also grew yearly.

But the sampler doesn’t include new developments. Georgium Sidus appears over to the right without an orbit, as if it doesn’t quite have a place in the existing order. Its distance from the sun and duration of revolution were known by the mid-1780s, however they don’t appear on the tables. The asteroids don’t appear at all. Maybe the diagram for the sampler was copied from an older book, published before 1781. That might explain why the sampler wasn’t finished. Who, in 1811, would want to spend weeks or months working on a picture of the Solar System that didn’t include the newest, most exciting planets?

Women didn’t find it easy to participate in late eighteenth century science. Experimentation and discovery were not easily compatible with the ideals of domestic femininity – but there were women who rejected these social expectations and became active and renowned. Botany was dominated by female amateurs, and education campaigner Maria Edgeworth considered chemistry to be particularly suitable. In 1798, Priscilla Wakefield wrote encouragingly,

‘there are many branches of science in which women may employ their time and talents, beneficially to themselves and the community, without destroying the peculiar characteristics of their sex, or exceeding the most exact limits of modesty and decorum’.[3]

One of the most successful was Caroline Herschel, William’s sister, who performed her own observations and discovered a number of comets. She even earned her own salary of £50 a year.

Girls interested in astronomy, if they were from rich families, could have private lessons. In the 1760s and 1770s this was quite common among daughters of the Bluestockings. Anne Emblin, born 1753, was tutored by James Ferguson, who wrote an account of their lessons as a set of Dialogues.[4]

The lessons provide a very detailed introduction and explanation of astronomy, staged as conversations between a girl called Eudosia (meaning ‘good thought’) and her brother Neander (‘new man’) who has returned from university at Cambridge.[5] Books, of course, were cheaper than tutors and Ferguson’s publication remained popular into the 1820s. Among the scientific talk of light particles and gravity, are commentaries like this one:

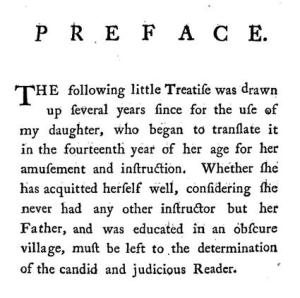

Another contribution to the body of astronomy books for girls appeared in 1787. Richard Wynne wrote his Geography and Astronomy textbook in English, and then it was translated into French and Italian by his daughter Catharine.[6] He explains:

In the early 1800s there was a general fear for the morality of England’s young women. The recent French Revolution had overturned the monarchy, the church, the family and the whole established way of life, and the establishment were terrified that revolutionary spirit would erupt on this side of the channel. Any change seemed threatening. If young women started thinking of their own education and interests above the needs of the family and the nation, this would surely lead to moral deterioration, collapse and revolution!

The Solar System sampler was made in this context of heightened fear, which makes the choice of inscription very interesting. The lines of text are taken from John Milton’s Paradise Lost.

These are thy glorious works, parent of good,

Almighty, thine this universal frame,

Thus wondrous fair; thyself how wondrous then!

Unspeakable, who sittest above these heavens

To us invisible or dimly seen

In these thy lowest works, yet these declare

Thy goodness beyond thought, and power divine

An apposite choice to caption the frame of the heavens. But Milton’s work was fraught with moral ambiguity – he was a great English poet with a clear Christian message, but he was also a republican who supported Cromwell in the Civil Wars.

In the next decade, both the Solar System and John Milton were drawn into the mainstream of educational practice, and in the process sanitised and moralised. The Religious Tract Society commissioned Thomas Dick to write their first astronomy pamphlets in the 1820s. Their diagram, so similar to the one on the sampler, includes all the new planets:

And in 1828 Eliza Weaver Bradburn published ‘The Story of Paradise Lost for Children’. This reduced version of the full text was framed as a mother telling Milton’s story, but avoiding the political aspects. This was a common method of introducing classical and literary works to children, especially girls, to avoid corrupting their virtue.[7]

In these books, access to knowledge is mediated by the specialist brother or father, or the watchful mother, in the domestic context of the lesson. And the most prominent Georgian female writer on astronomy used the same format.

Margaret Bryan published three books of Natural Philosophy for ‘the use of schools and private families’, and she ran a small college for ‘young ladies’ in London. Teaching gave Margaret a way to write and publish scientific work, without threatening to overstep the bounds of ‘modesty and decorum’. The introductions to her books overflow with maternal sympathies and religious fervour. She assures her pupils that learning science will…

‘arm you with a perpetual talisman, which… will secure you from all pernicious doctrines, and guard your religious an moral principles against all innovations. Omit no opportunity of applying the lessons they impart to perfect every thing that gives either value or grace to the female character… Cull the sweets of religion, as you rove through the flowery paths of Natural Philosophy’[8]

Bryan’s descriptions of natural phenomena continually reinforce the domestic, conservative point of view:

‘In the centre of the solar system… is placed the sun, like the father of a family, surrounded by bodies dependent on his emanations. These are called planets.’[9]

Marina Benjamin has written that Bryan’s references to herself as a mother, teacher, and amateur, and her overstated respectability and piety, made it possible for her to stretch the boundaries of acceptability in other ways.[10] By being overtly, even overly, feminine, she could publish her own work. Indeed, Bryan was well-received and reviewed in astronomical journals. To speak as a woman in science, she had to find a different, feminine language.

Writing about women shell collectors and embroiderers, Ariane Fennetaux has made a similar point about crafts. They ‘allowed women to experiment with fields and ideas that were traditionally associated with masculine pursuits’.[11] Women developed serious expertise in conchology while producing ‘feminine’ shell sculptures and grottos.

My experience of the uncanny with the Solar System sampler may have arisen from this same tension of scientific ideas in a craft form. This might also be a tension between what women wanted to do and how they had to do it – needlework was a way for this young girl to represent scientific, conventionally masculine ideas, without reproach. The resulting object refuses to fall easily into either category of craft or science, and simultaneously calls into question the associated ideas of what women should do and how they should do it.

[1] Rozsika Parker describes how the process of making a sampler using thousands of tiny, planned stitches was ‘intrinsically disciplining’ in her groundbreaking book about female embroidery, The Subversive Stitch: Embroidery and the Making of the Feminine (1984)

[2] ‘A Letter from William Herschel’, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, Vol. 73 (1783) available at http://www.jstor.org/stable/106476 . As we know, this name didn’t stick for long. Understandably, French astronomers after the Revolution refused to use the name of a monarch for a heavenly body, so ‘Herschel’ was tried for a while, but eventually ‘Uranus’ caught on.

[3] Priscilla Wakefield, Reflections on the Present Condition of the Female Sex; with Suggestions for Its Improvement (1798)

[4] E Henderson, Life of James Ferguson, in a brief autobiographical account and further extended memoir, with notes (1870)

[5] James Ferguson, An easy introduction to astronomy for young gentlemen and ladies (1768)

[6] Richard and Catharine Wynne, A short introduction to geography: to which is added an abridgement of astronomy (1787)

[7] Julie Pfeiffer , ‘”Dream not of other worlds”: Paradise Lost and the Child Reader’ in Children’s Literature, Volume 27 (1999)

[8] Margaret Bryan, Lectures on Natural Philosophy: The result of many year’s practical experience of the facts elucidated (1806)

[9] Margaret Bryan, A Comprehensive Astronomical and Geographical Class Book, for the use of schools and private families (1815)

[10] Marina Benjamin, ‘Elbow Room: Women writers on Science, 1790 – 1840’, in Science and Sensibility: Gender and Scientific Enquiry, 1780 – 1945 (Basil Blackwell, 1991)

[11] Ariane Fennetaux, ‘Female Crafts: Women and Bricolage in Late Georgian Britain, 1750-1820’ in Women and Things 1750-1950: Gendered Material Strategies (Ashgate 2009)

What an intriguing object and fantastic post; so much information beautifully written and so much food for thought!

[…] mentioned on the Collecting Childhood blog it’s quite an unusual sampler. It doesn’t employ any of the floral motifs or […]

[…] Star-gazing girls of Georgian England. […]

Fascinating study of samplers, women’s education at the turn of the 18thc, scientific knowledge thought suitable for girls in particular. Jane Austen was writing her novels of course, at the same time.

[…] blog of the Victoria and Albert Museum of Childhood, where the sampler is held, has an excellent post about the piece and its historical […]

[…] out this feature on stargazing girls in Georgian England, including an embroidery sampler of the solar system from […]

[…] Although they weren’t on display, the Museum an incomplete astronomy-themed sampler, which is pictured and discussed in this post: Star-gazing girls of Georgian England. […]

I found this lovely post by way a link from Nordic Needle’s facebook page. The poor abandoned sampler makes me think of a poor girl telling her mom, “I don’t WANT to make a sampler, I want to make star charts like my brother!”

“A young lady has to learn to embroider. How about an astronomical sampler?”

“Well, if I have to…”

Mom tracks down a star chart from a book, has the canvas custom made and, feeling like mother of the year, presents it to her daughter.

“But, Mummy, this star chart isn’t right, it doesn’t have all the planets on it!”

“Just work on the damn sampler.” (Or the ladylike Georgian equivalent.)

The sampler is misplaced by the daughter as soon as she can manage it. I feel for both of them!

What an interesting blog post – I find the rights of women in the late eighteenth century – early nineteenth century absolutely fascinating (Wollstonecraft, of course, a favourite!) so this exploration of a domestic topic with the world of science is absolutely illuminating. Thanks for sharing!

Wow, needlepoint is real dedication. All I do is tote a blanket and a pair of binoculars up to the top of the hill after sunset. The only samplers I involve myself with are the kind that say Whitman’s on them. Which gives me an idea about what to bring to the next star party….

Loved the post! So informative and wholly inspiring.

But the two do strangely go together. Look at the scientists of the day… if anything it reveals the hobbyhorse of science, for those who could afford it, as what it truly was at the time. Not to say that eighteenth and nineteenth century science wasn’t astounding.

Certainly not a star gazer, but I am a candle gazer.

Great post! I have never thought about it before. Seeing the freedom of female students right now, we should be grateful.

Fascinating post. I appreciate your hard work in presenting the subject in a rich and scholarly manner. What skill women (and girls) had to employ to enjoy “masculine” pursuits without being accused of losing their “femininity.”

As a woman who has a love for science, and not fond of inhibiting social expectations, I found your post to be quite fascinating. Congratulations on being Freshly Pressed.

What interesting art as well!

Great article! The astronomy-themed sampler is so cool — more kids should know about things like that, so even girls who idolise femininity are reminded that they can be feminine and sciencey all at once!

This was so informative – a piece of history I knew nothing about. Thanks!!

Sounds like the kind of embroidery I’d do in that era. If you’re going to spend hours doing needlework, why not map out the solar system?

I just wanted to say thank you for writing this post. I found it absolutely fascinating!

[…] Star-Gazing Girls of Georgian England […]

[…] can read more about this intriguing sampler here and […]

[…] A sampler from the Museum of Childhood: https://collectingchildhood.wordpress.com/2013/03/08/star-gazing-girls-of-georgian-england/ Five year old girl finds a new dinosaur: http://www.themarysue.com/five-year-old-discovers-dinosaur/ […]

[…] Museum of Childhood via Slate. […]

[…] Star-gazing girls of Georgian England. […]

[…] blog post from the Museum of Childhood highlights a particularly fascinating instance of material culture: a nineteenth-century […]

[…] Star-Gazing Girls of Georgian England (collectingchildhood.wordpress.com) […]

[…] Star-gazing girls of Georgian England […]

[…] Guess what that is? A never-finished Regency-era sampler depicting the solar system! Or so they say over at the Museum of Childhood, where a wonderful blog post about Georgian-era asterism-themed samplers awa… […]